March 10, 2024 – SEVINÇ BERMEK AND ASLI UNAN

Previously published on VoxEU on March 8, 2024

Violence against women entails great psychological, physical, and socioeconomic costs. Prevailing victim-blaming norms are an impediment to social change. This column uses an experiment to uncover the different behavioural mechanisms that drive policy and attitudinal change and are working in a complementary fashion. The findings are good news for introducing welfare-improving social change as they suggest a stepping-stone approach to changing policy and norms regarding gender-based violence.

Violence against women, particularly intimate partner violence (IPV), is a pervasive global issue with severe psychological and socioeconomic consequences (Brioschi et al. 2016). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than one in three women worldwide have experienced IPV (WHO, 2021). One in three femicides each year is committed by an intimate partner, a problem exacerbated by the recent pandemic (Bhalotra 2020). Political leaders and law enforcement ignore or downplay the IPV issue, often blaming the victims (Dahir 2024). The economic cost is staggering, estimated at €366 billion per year in the EU, representing a 6% ‘tax’ on disposable income (EIGE 2021). Despite societal progress, gender-based violence persists even in economically advanced nations, highlighting the urgent need to address this issue.

To combat violence against women effectively, it is crucial to understand societal attitudes and norms that either perpetuate or deter such violence. Victim-blaming plays a significant role in this, extending beyond gender-based violence to contexts like poverty, homelessness, or political violence (Vice 2021, The Guardian 2017). This pattern of assigning fault or responsibility to victims in situations where they lack agency is closely tied to social norms and has implications for policy change.

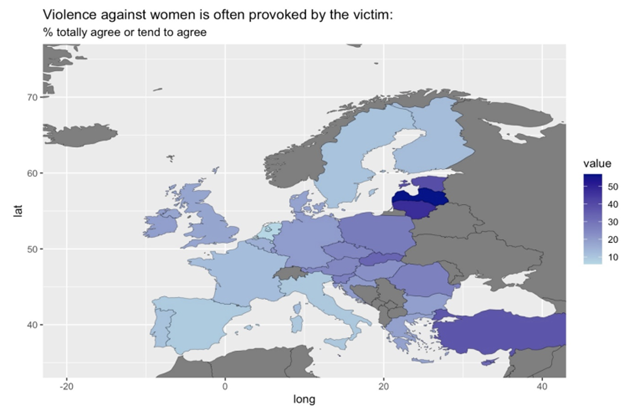

Despite its far-reaching implications, the role of social norms, especially victim-blaming norms, and its relation to gender-based violence remains understudied in economics and political science. Using Eurobarometer data, we shed light on this phenomenon. Figure 1 illustrates prevalent victim-blaming attitudes in Central Eastern European (CEE) countries and Baltic countries, potentially linked to the collapse of Soviet-styled morality after the Cold War (Zajda 1988). Conservative values in the former Soviet Union and CEE, reacting to rapid changes post-socialism, the end of the Cold War, and rapid neoliberalisation, contribute to victim-blaming (Laruelle 2022, Khmelnitskaya et al. 2023, Sätre et al. 2023).

Figure 1 Victim-blaming attitudes in Europe

Notes: Grey areas on the chart indicate missing data for those countries. The data is derived from Eurobarometer 85.3, 2016. The Turkish data is derived from our survey, employing a similar item to measure victim-blaming attitudes. Specifically, the item read, ‘The woman shouldn’t have provoked her husband,’ within the context of intimate partner violence (IPV).

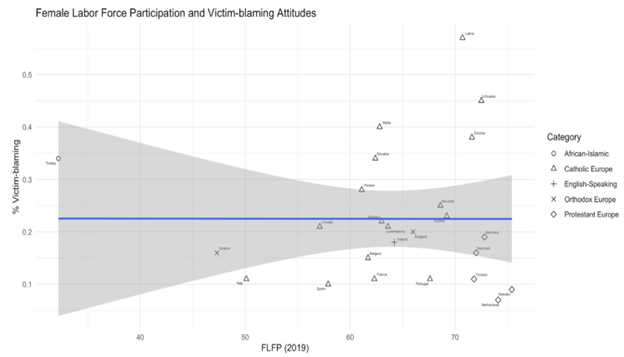

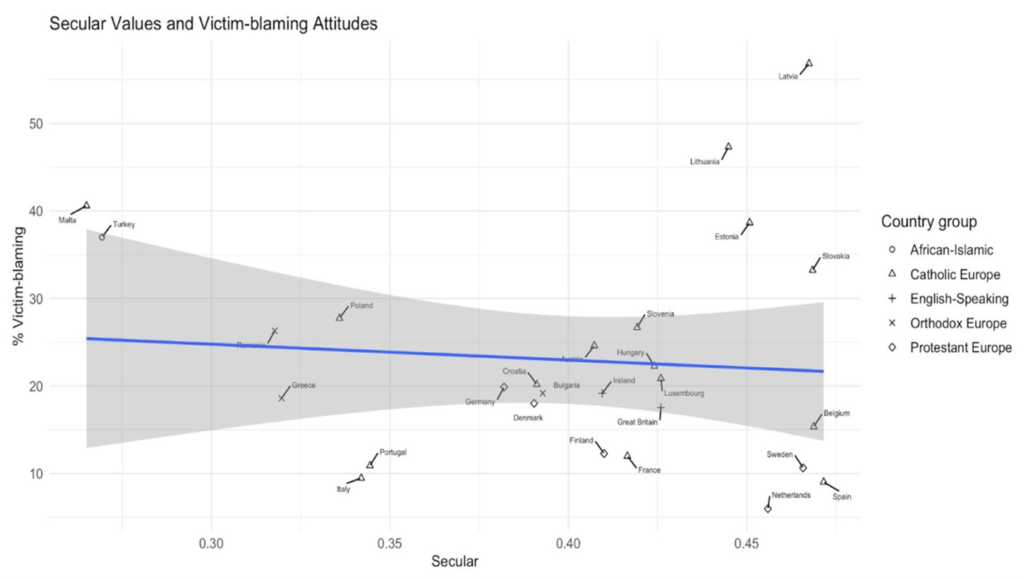

Interestingly, cultural and socioeconomic factors traditionally associated with gender-based violence and victim-blaming norms do not explain variations in victim-blaming attitudes. Figure 2b indicates no significant difference between victim-blaming norms based on female labour force participation. Regional differences are more prominent between Western Europe and Central Eastern European countries and Baltic countries. Turkey constitutes an outlier in this figure due to its low female labour force participation. Figure 2c shows no significant differences in victim-blaming attitudes concerning secular values.

In our recent work (Bermek et al. 2023), we assert that victim-blaming attitudes, where individuals justify or tolerate intimate partner violence, contribute significantly to the social acceptability of gender-based violence. Figure 2a shows a positive relationship between victim-blaming attitudes and social acceptability/justification of gender-based violence, emphasising the critical policy importance of understanding and addressing victim-blaming attitudes to curb gender-based violence.

Figure 2a Victim-blaming attitudes in Europe and violence against women

Notes: The country categorisation follows the World Values Survey (WVS). Data on violence against women (WAV) is sourced from the World Values Survey Wave 7 (2017-2022) using the question: “Do you think violence against women can always be justified, never be justified, or something in between (1-10)?” The victim-blaming variable, expressed as percentages per country, is adopted from Eurobarometer 85.3 (2016). Specifically, the percentages are calculated based on responses ‘completely agree’ and ‘agree’ to the statement that ‘Violence against women is often provoked by the victim.’ The Turkish data is derived from our survey, employing a similar item to measure victim-blaming attitudes. Specifically, the item read, ‘The woman shouldn’t have provoked her husband,’ within the context of intimate partner violence (IPV).

Figure 2b Relationship between victim-blaming attitudes and female labour force participation

Notes: The country categorisation follows the World Values Survey (WVS). The victim-blaming variable, expressed as percentages per country, is adopted from Eurobarometer 85.3 (2016). Specifically, the percentages are calculated based on responses ‘completely agree’ and ‘agree’ to the statement that ‘Violence against women is often provoked by the victim.’ The Turkish data is derived from our survey, employing a similar item to measure victim-blaming attitudes. Specifically, the item read, ‘The woman shouldn’t have provoked her husband,’ within the context of intimate partner violence (IPV). Female labor force participation data is extracted from Eurostat (2019).

Figure 2c Relationship between victim-blaming attitudes and culture

Notes: The country categorisation follows the World Values Survey (WVS). Secular vs. traditional values is obtained from WVS (2019). The victim-blaming variable, expressed as percentages per country, is adopted from Eurobarometer 85.3 (2016). Specifically, the percentages are calculated based on responses ‘completely agree’ and ‘agree’ to the statement that ‘Violence against women is often provoked by the victim.’ The Turkish data is derived from our survey, employing a similar item to measure victim-blaming attitudes. Specifically, the item read, ‘The woman shouldn’t have provoked her husband,’ within the context of intimate partner violence (IPV).

To deepen our understanding of these aggregate patterns, we complement this cross-country perspective with an experimental study in Turkey, a context marked by prevalent gender-based violence. Our study seeks to address two primary questions: Why do victim-blaming attitudes persist? And how do social norms 1 impact policy preferences and individual behaviour regarding intimate partner violence?

Contrary to common belief about the role of religion, economic factors, and culture, moral considerations emerge as the primary factors influencing policy and behaviour change. Victim-blaming norms intricately connect with moral considerations (Niemi and Young 2016) of a universal nature (Cappelen et al. 2022). Two core mechanisms – change in attitudes via correcting misperceptions about victim-blaming norms, and change in policy preferences and behaviour via morality – play a crucial role in preventing IPV.

To explore these mechanisms, we conducted a survey experiment involving a representative sample of 3,600 respondents in Turkey, using both between- and within-subject designs and within-group randomisation. Participants were monetarily incentivised to form higher-order beliefs (‘perceived norms elicitation’), following the method developed by Bicchieri and Xiao (2009) and compare these with their own attitudes. We randomised the order in which participants considered their attitudes and perceived social norms.

Our study reveals three main findings:

1 Attitudes and behaviour are affected by different behavioural channels

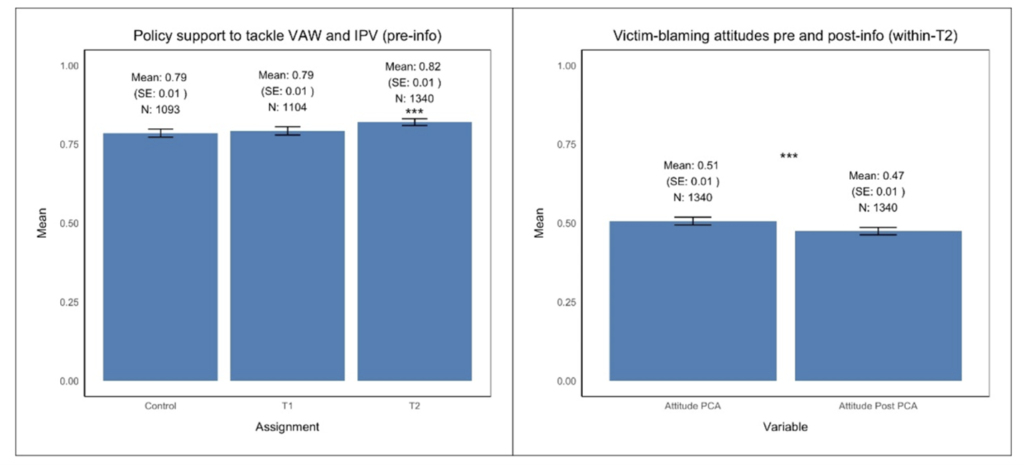

In the study, we follow a two-path strategy. First, we experimentally incentivised our subjects to form higher-order beliefs about societal victim-blaming norms by prompting them to think about and assess others’ attitudes after presenting a fictional IPV scenario. This process, forcing subjects to make relative moral evaluations, acted as a self-nudge on the salience of victim-blaming norms, significantly altering policy preferences and quasi-behavioural outcomes (donation and intention to act). Nonetheless, this nudging exercise had minimal impact on changing respondents’ own victim-blaming attitudes. The latter proved more responsive to information provision (our second experimental condition, consistent with Bayesian update), 2 correcting misperceptions about the prevailing social norm and leading to significant changes in participants’ own attitudes, as shown in Figure 3. Our findings reveal that attitudes are deeply held and only change in response to ‘hard’ information (‘belief updating’) that corrects subjects’ misperceived beliefs. In contrast, aligned with theories of social anchoring (Tversky and Kahneman 1974, Lewin 1947), policy preferences (and elicited behaviour) appear to be more malleable and respond to soft nudges, such as stimulating respondents to generate higher-order beliefs on society’s victim-blaming attitudes.

Figure 3 Primed victim-blaming norms versus belief updating: Change in policy preferences and attitudes

Notes: On the left side, policy PCA serves as a comprehensive item of policy support for addressing gender-based violence issues. Assignment group T2 pre-info represents policy preferences after priming victim-blaming norms but before providing respondents with information about the actual norm. Therefore, it uniquely captures the impact of self-reflection and assessment in alignment with societal victim-blaming attitudes. On the right-hand side, we illustrate attitude changes within T2 both before and after information updates, showing a statistically significant decrease in victim-blaming attitudes among respondents’ post-information update.

2 The mechanism of moral dissonance

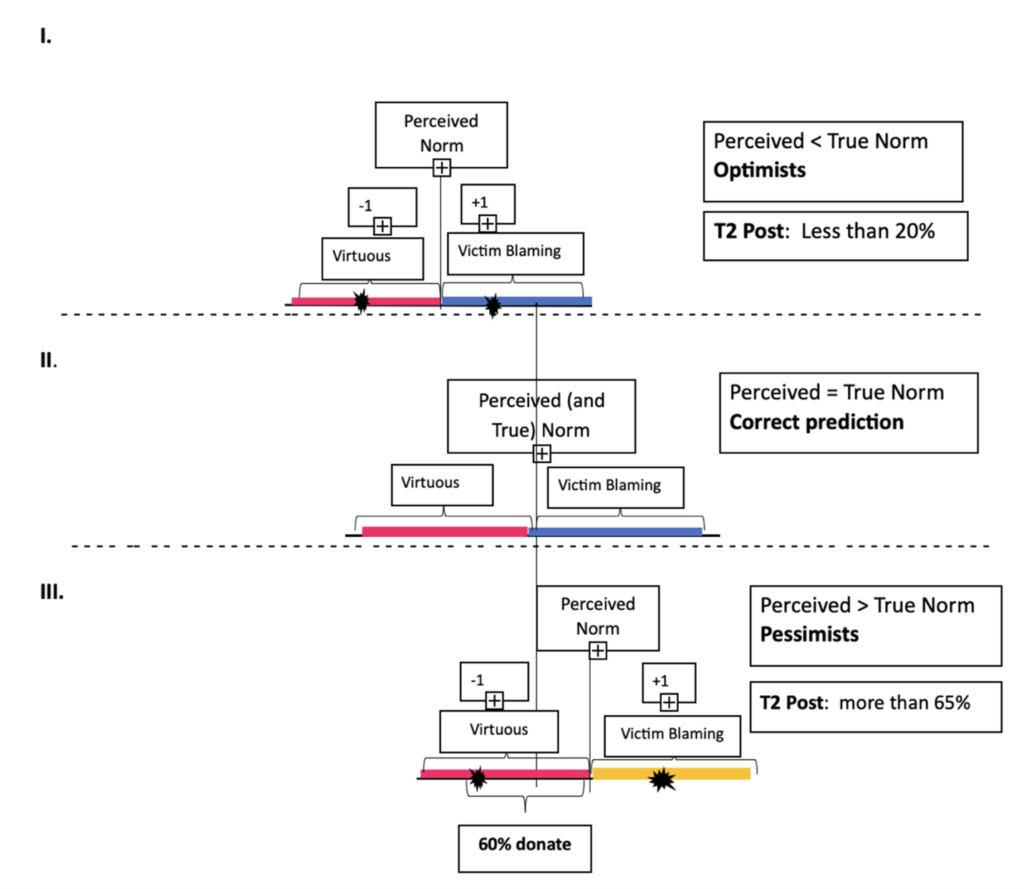

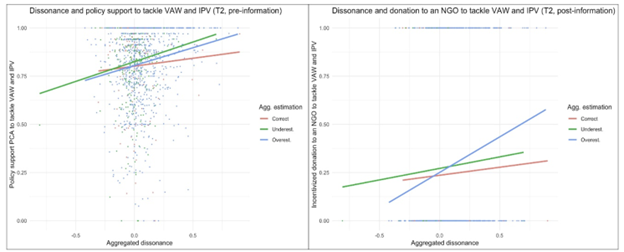

In our study, we instrumentalise the concept of moral dissonance to capture the effects of priming the formation of beliefs about social norms. Moral dissonance, 3 defined as the difference between individuals’ own attitudes and perceived victim-blaming norms, prompts relative moral comparisons (“my values” versus “my perception of others’ values”), motivating individuals to demand policy change and change their behaviour. Figure 4 visually represents this relationship, indicating a true norm where there is no distance between individuals’ perception of the victim-blaming norm and the actual norm. We categorised norm prediction into two core categories: pessimistic (over-estimators) and optimistic (under-estimators), further sub-categorised based on their own attitudes (either victim-blaming or virtuous). As demonstrated in Figure 4, a positive (+1) value implies that the respondent sees themselves as ‘more virtuous’ (or morally superior) compared to the average society member – they believe that society at large espouses more victim-blaming attitudes than themselves; a (-1) value implies the opposite. As a result, we achieve a victim-blaming/virtuous map of society on an axis of pessimistic–optimistic. Figure 4 illustrates that 65% primed respondents overestimated true societal norms, with about 20% underestimating them. Moreover, we find that moral dissonance corresponds with increased policy support for addressing gender-based violence and a willingness to donate bonus earnings to NGOs working on such issues. Specifically, 60% of respondents who donate fall into the virtuous and over-estimator category. This group is more likely to support policy changes for tackling gender-based violence and to donate their bonus earnings to a feminist NGO, as shown in Figure 5. This positive relationship is more apparent for the over-estimator group (blue line with the label 1) than for the two other groups that underestimated (green line with the label -1) or accurately targeted the true norm (red line with label 0), as shown in aggregated estimations.

Figure 4 The partition of the information space

Notes: In the initial stage of the experiment subjects only form higher-order beliefs (and express their own attitudes) without knowing their accuracy (i.e. they do not know to which partition of the three they are). Moral dissonance = difference between respondents’ perception of the norm and their own victim-blaming attitudes (-1 implies own attitude less victim-blaming than perceived norm, while +1 the opposite). In the second part (post information update) only subjects in T2 learn whether they over/under or correctly estimated the social norm and to which space they belong to.

Figure 5 Morality dissonance, policy support, and donation

Notes: Aggregated continuous dissonance measures the difference between an individual’s personal victim-blaming attitudes and their perception of societal norms. Aggregated estimation is a variable reflecting whether respondents have underestimated (-1), overestimated (1), or accurately estimated (0) the societal victim-blaming norm. Donation serves as a measure of behavior change for addressing gender-based violence issues. Policy support PCA captures a bank of variables that captures policy preferences to tackle WAV and IPV.

3 Directional asymmetry and gender effects

We observe a significant directional asymmetry behind the moral dissonance effect. Individuals perceiving themselves as less tolerant of victim-blaming norms, such as those identified as virtuous and over-estimators in Figure 4, drive the change in policy behaviour and actions (e.g. through donation). Moreover, in the gender-based heterogeneity analysis of moral dissonance, women categorised as victim-blaming and over-estimators of the true norm (pessimistic) in Figure 4 demonstrate higher levels of moral scepticism towards their peers and are less likely to donate to the feminist NGO. This highlights that women with more victim-blaming tendencies towards other women hold a judgemental position and are less likely to support actions favouring norm change. This suggests a sentiment of self-enhancing moral superiority behind the documented policy and behavioural changes. Additional analysis of gender-specific effects within the T2 group reveals a gender-specific effect on women’s likelihood to take action, with less pronounced effects on men’s behaviour.

Implications and policy recommendations

Short-term versus long-term effects

Our findings suggest that correcting misperceptions about victim-blaming norms can impact on individuals’ attitudes towards IPV, but may not immediately translate into changes in policy preferences or behaviour. Policy changes seem more responsive to softer nudges, emphasising the need for both short-term and long-term strategies in combating gender-based violence. While correcting misperceptions is essential for attitude change, additional measures are necessary to bridge the gap between changed attitudes and policy support and behavioural outcomes, emphasising a multi-faceted approach.

Beware of asymmetry

Caution should be exercised due to asymmetry in responses. Pessimistic and over-estimator individuals become less tolerant of victim-blaming attitudes with accurate information – a positive outcome. However, underestimators, holding optimistic views, may become more tolerant. Policymakers must carefully assess the potential backlash and design interventions addressing both groups for a comprehensive approach to changing norms.

Tailored approaches

Our study highlights the importance of tailored approaches to address victim-blaming norms and behaviours related to IPV. Gender-specific differences suggest one-size-fits-all interventions may be insufficient. Women, exhibiting higher moral scepticism, are more likely to take action when primed with victim-blaming norms, indicating the need for gender-specific strategies. Tailored approaches can maximise effectiveness by addressing existing dynamics within different demographic groups.

Conclusion

Our study provides the first experimental evidence on victim-blaming norms, their impact on attitudes, and how this relationship shapes policy preferences and behaviour in combating IPV. Recognising perceptions of victim-blaming norms and moral dissonance is crucial for positive policy change. While priming norms may not directly affect attitudes, it can indirectly shape policy support. Correcting misperceived norms is crucial for changing attitudes, but additional strategies are needed to bridge the gap between attitudes and behavioural outcomes. Our findings provide insights into social policy dynamics, laying the groundwork for more effective strategies against gender-based violence.

Sevinç Bermek is Lecturer in International Political Economy at King’s College London.

Asli Unan is Assistant Professor of Political Economy at University Of Amsterdam.

Image by freepik

References

Bicchieri, C and E Xiao (2009), “Do the right thing: but only if others do so”, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 22: 191–208.

Bermek, S, K Matakos and A Unan (2023), “Victim-blaming Social Norms and Violence Against Women: Correcting Misperceptions or Morality Drive Policy and Behavior Change?“, SSRN.

Bhalotra, S (2020), “A shadow pandemic of domestic violence: The potential role of job loss and unemployment benefit”, VoxEU.org, 13 November.

Brioschi, B, E La Ferrara and A Alesina (2016), “Violence against women: A cross-cultural analysis for Africa”, VoxEU.org, 25 March.

Cappelen, A W, B Enke and B Tungodden (2022), “Moral universalism: Global evidence”, NBER Working Paper No. 30157.

Dahir, A L (2024), “Shaken by Grisly Killings of Women, Activists in Africa Demand Change”, The New York Times, 19 February.

EIGE – European Institute for Gender Equality (2021), “Gender-based violence cost 366 Billion”, 7 July.

Gulesci, S, S Jindani, E La Ferrara, D Smerdon, M Sulaiman and H Young (2021), “A stepping stone approach to understanding harmful norms”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 15776.

Khmelnitskaya, M, A Sätre and U Pape (2023), “Flexible Authoritarian Governance in Russia: The Politics of Ideas on Family Policy”, Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 31(3): 335-362.

Laruelle, M (2023), “A grassroots conservatism? Taking a fine-grained view of conservative attitudes among Russians”, East European Politics 39(2): 173-193.

Lewin, K (1947), Group decision and social change, Readings in Social Psychology, Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Niemi, L and L Young (2016), “When and why we see victims as responsible: The impact of ideology on attitudes toward victims”, Personality and social Psychology Bulletin 42: 1227–1242.

Sätre, A-M, Y Gradskova and V Vladimirova (2023), Post-Soviet Women: New Challenges and Ways to Empowerment, Palgrave Macmillan.

Te Brake, H., & Nauta, B. (2022), “Caught between is and ought: The Moral Dissonance Model”, Frontiers in Psychiatry 13, 906231.

The Guardian (2017), “The big stigma is it’s the homeless person’s fault”, 7 August.

Tversky, A and D Kahneman (1974), “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty”, Science 185: 1124-1131.

Vice (2021), “A Complex Systems Theorist Explains Why the Poor Aren’t to Blame for Poverty”, 25 January.

Zajda, J (1988), “The Moral Curriculum in the Soviet School”, Comparative Education 24(3): 389-404.

WHO. (2021), “Devastatingly pervasive: 1 in 3 women globally experience violence”, 9 March.

Footnotes

- For our research, we consider the definition of Bicchieri (2006) who defines the norms as “a rule of behaviour such that individuals prefer to conform to it on condition that they believe that (a) most people in their reference network conform to it (empirical expectation), and (b) that most people in their reference network believe they ought to conform to it (normative expectation)”. In our research study, we particularly focus on a subset of social norms that we named them as victim-blaming norms.

- Bayesian update occurred via informing true victim-blaming norms in the society (as well as their own attitudes) to respondents.

- The moral dissonance model (MDM) is based on the dissonance between ‘is’ and ‘ought’. The MDM model combines two core elements; when confronted with a morally ambiguous situation, the individual intuitively tries to make sense of it before responding. This reaction constitutes the actual behaviour. After the initial response, people will try to rationalize their behaviour to themselves (individually) and others (socially). Moral dissonance occurs when the displayed behaviour is experienced to conflict with a morally desirable behaviour (ought). Hence, it is the thought of an individual as I should have acted otherwise (Te Brake and Nauta, 2022). Unlike this model, which reflects solely the difference between their behaviour and the socially acceptable behaviour. In our model, the moral dissonance also captures individuals’ perception of others in the society and hence it captures the difference between their own attitudes and their perceived norms.

0 Comments