October 5, 2024 – MALEKE FOURATI

Previously published on VoxEU on September 30, 2024.

Education is recognised as a crucial factor in breaking the cycle of poverty. This column examines how historical exposure to colonial public primary schools in Tunisia influences medium- and long-run literacy rates. It finds that increased enrolment of Tunisian students during the colonial period significantly boosted literacy decades later, while the enrolment of European pupils did not have a lasting influence. This result is mainly driven by older generations and tends to fade away for younger ones. Post-independence investments improved educational access and reduced spatial disparities.

“For us, education is a social function, i.e. a fundamental factor in our collective entity, and a responsibility that must be fulfilled equally by the state, the teacher and the learner.”

Habib Bourguiba, First President of Tunisia (1957-1987) 29 June 1968 (authors’ translation)

In Tunisia, the remnants of colonial-era schools stand as a testament to a century-old educational legacy that continues to shape lives. In 2000, the United Nations established universal primary education as the second Millennium Development Goal, recognising education as a crucial factor in breaking the cycle of poverty. However, for many countries, including Tunisia, this goal is not just a contemporary issue; its roots extend deep into the past, shaped significantly by their colonial history. This raises an important question: How can we address the lingering effects of colonialism to improve education?

In many countries across the globe, the level of human capital, one of the drivers to economic performance, is partly imputable to policies implemented by European settlers during the early 20th century (Glaeser et al. 2004). In fact, whatever the settlers brought to their colonies – extractive institutions, civil versus common laws, etc. – it proved to have had a lasting imprint on contemporary economic development (Acemoglu et al. 2014, Nunn 2009).

As a matter of fact, a strand of the economic literature studies the effect of the colonial persistence on socioeconomic outcomes. Colonial institutions have been considered as the workhorse of such persistence (Acemoglu et al. 2014, Acemoglu and Robinson 2006, Dell 2010, La Porta et al. 1999). Banerjee and Iyer’s seminal work on India find that differences in historical property rights led to different contemporary economic outcomes (Banerjee and Iyer 2005). In Brazil, Rocha et al. (2017) show that a settlement policy that attracted more educated immigrants in some municipalities at the turn of the 20th century resulted in higher levels of schooling and income per capita a century later.

Huillery (2009) studies the long-term effects of colonial investments in education, health, and infrastructure in French West Africa. She highlights the persistence of investment as the main mechanism, meaning that current public investments are predominant in areas where colonial investment already prevailed. Dupraz (2019) uses the partition of Cameroon to study long-term educational outcomes. He finds that, in 2005, individuals born after 1970 were more likely to have completed high school and to have a high-skilled occupation if they were born in the formerly British part of the country.

In a forthcoming paper (Ben Salah et al. 2024), my co-authors and I exploit spatial variations in exposure to colonial public primary education to estimate the weight of colonial history on education. Tunisia, under French protectorate from 1881 to 1956, saw an expansion of primary schools aimed at increasing the enrolment rate for both French and Tunisian pupils (Sraieb 1993). By examining historical data on school locations, enrolment rates, and subsequent population censuses, coupled with literacy rates from 1984 and 2014, we found that increased exposure to colonial public primary education significantly boosted literacy decades later. Specifically, a 1% rise in enrolment of Tunisian pupils in 1931 is linked to nearly 1.8 percentage point higher literacy rates in 2014. This translates into an additional 889 individuals per district being literate in 2014.

In Tunisia, unlike Brazil, European settlers massively deserted the country after independence. This implies that persistence in the Tunisian context is solely carried on by the local population and not a mixture of indigenous and European settlers. In addition, Tunisia has a highly homogeneous population in terms of religion and ethnicity, which limits the threat of potential confounders. 1 Furthermore, we go beyond studying the effect of colonial investments in public primary education, which could have benefited only settlers, and rely on a measure of the direct exposure to public primary education by estimating the enrolment rate of Tunisian pupils and controlling for colonial investment. In a placebo exercise, we examine the lasting influence of the enrolment rate of European pupils in 1931 on current educational outcomes. We do not find any correlation. This indicates that it is truly the exposure of Tunisian pupils that matters.

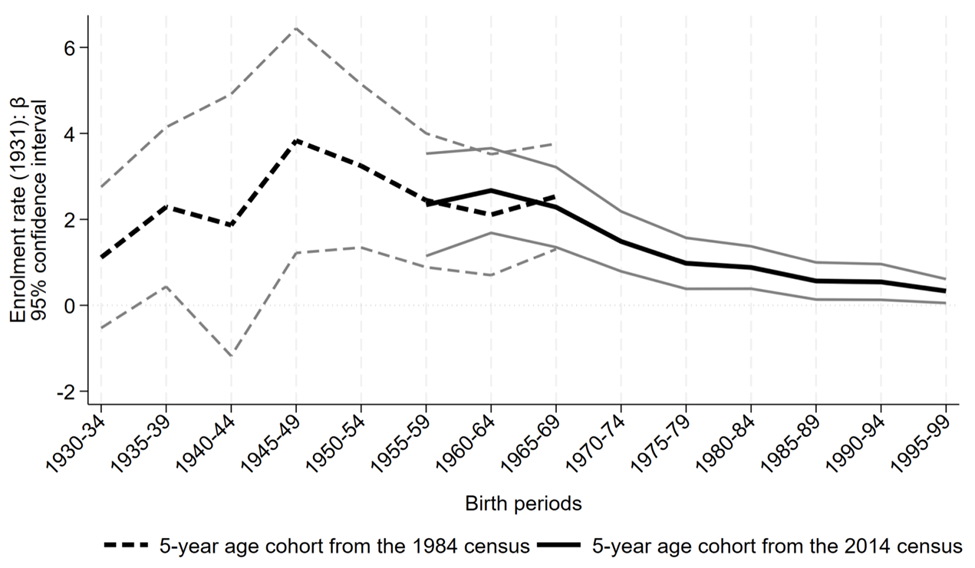

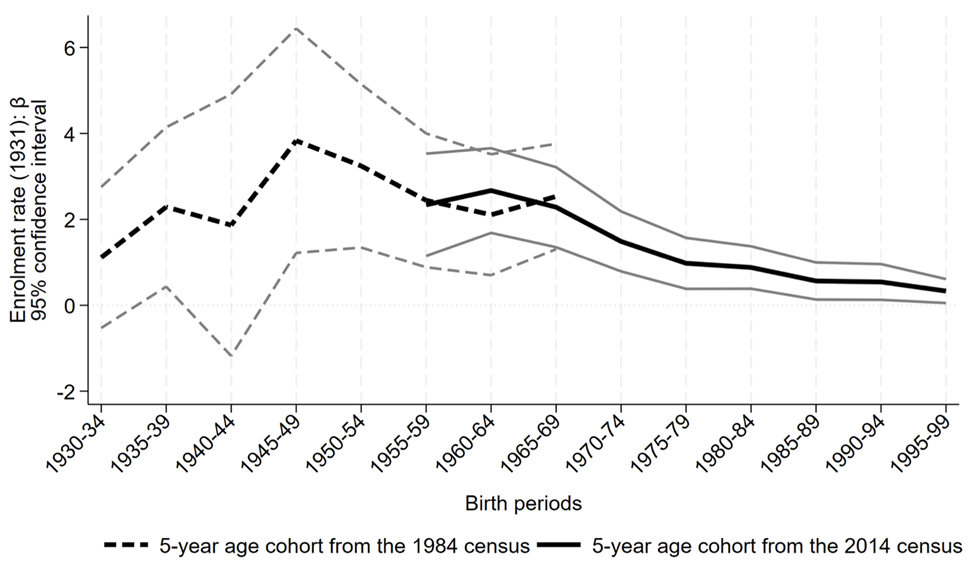

Finally, our dataset provides a decomposition by age cohorts. Figure 1 plots the regression coefficients by age cohort. The relation with the exposure to colonial public primary education and the likelihood of completing primary education peaks for the age cohort born in 1945–49 who started to attend primary school in the last years of the colonial period. It then slowly declines for all age cohorts born thereafter, reaching a 0.29 percentage point increase in the share of males completing primary school for the age cohort born in 1995–99. While this result may seem to contradict the discussion presented above, it is hardly surprising given that Tunisia had achieved near-universal primary education by the end of the 20th century – 96.4% for the age cohort born in 1995–99. This mirrors findings from other studies, like those of Chaudhary and Garg (2015) in India, where effective policies eventually countered colonial educational disadvantages.Figure 1 Dynamic effect of exposure to colonial public primary education

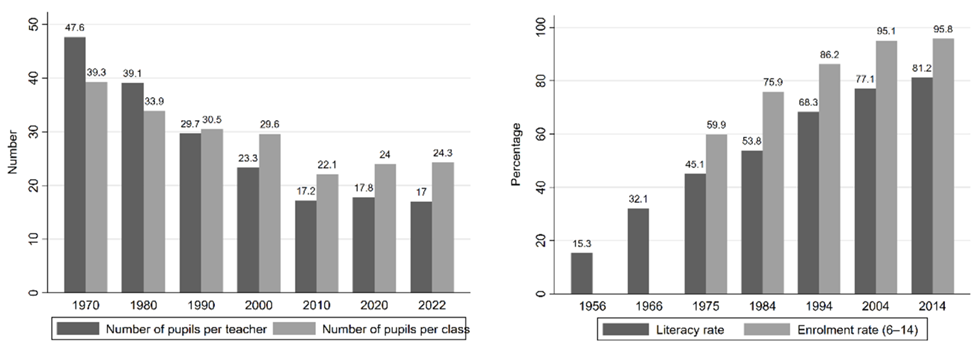

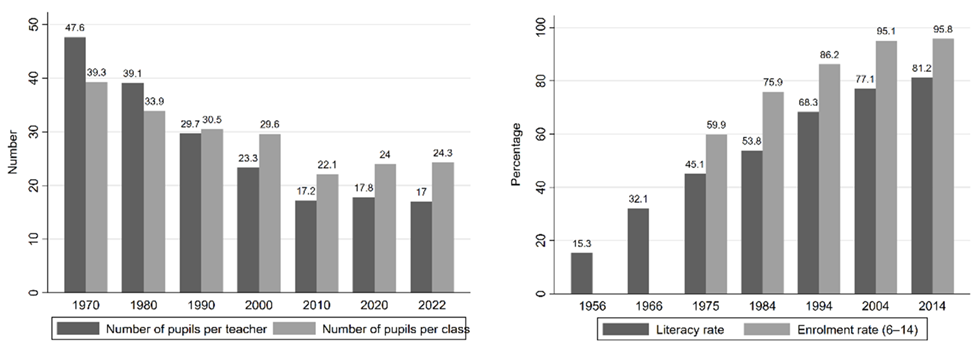

Following independence, Tunisia’s government had prioritised education, aiming for universal primary enrolment by 1966. In 1958, spatial disparity remained significant: the enrolment rate ranged from as low as 13% in the governorates of Beja and Kairouan, remote regions of Tunisia, to 42% in Tunis, the capital city. In an effort to overcome structural difficulties, the government implemented the first major educational reforms in 1958. In subsequent years, the budget allocated to education grew from 18% in 1958-9 to 32% in 1967. The second major reform, carried out between 1989 and 1991 made school compulsory for children aged between 6 and 16 years old and further stimulated investment in education. As evidenced by Figure 2, primary school enrolment rate was capped at around 60% in the 1970s, which slowed the spread of literacy among the population. However, the Tunisian government pursued its investments in education which continued to make significant progress throughout the 1980s and the 1990s. By 1994, the primary school enrolment rate had reach 86.2%, and by 2014, 99% for children aged 6–11 and 95.8% overall enrolment rate. The continuous efforts made by post-colonial governments to provide universal primary education across the country took around 50 years, and downsized spatial disparities inherited from the colonial education. However, these gains came with challenges, particularly concerning the quality of education.

Figure 2 Educational investment and outcomes in Tunisia, 1956-2014

In conclusion, while Tunisia’s colonial educational legacy still impacts its society, the country’s post-independence reforms show that history is not destiny. Effective policies and sustained investments eventually reduce the spatial disparities inherited from the colonial schooling system for new generations. As we look to the future, the focus must shift to ensuring the quality of education, reflecting the ongoing challenge of the Millennium Development Goals.

Maleke Fourati is an Associate Professor at the South Mediterranean University – Mediterranean School of Business (SMU-MSB), currently on leave at the University of French Polynesia.

References

Acemoglu, D, F A Gallego and J A Robinson (2014), “Institutions, human capital, and development,” Annual Review of Economics 6(1): 875-912.

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson and J A Robinson (2001), “The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation,” American Economic Review 91(5): 1369-1401.

Acemoglu, D, and J A Robinson (2005), Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy, Cambridge University Press.

Álvarez-Aragón, P, C Guirkinger and P Villar (2023), “Legacy of Colonial Education: Unveiling Persistence Mechanisms in the DR Congo”, No. 2305, University of Namur, Development Finance and Public Policies.

Banerjee, A and L Iyer (2005), “History, institutions, and economic performance: The legacy of colonial land tenure systems in India,” American Economic Review 95(4): 1190-1213.

Ben Salah, M, C Chambru and M Fourati (2024), “The colonial legacy of education: evidence from of Tunisia,” Working Paper No. 411, University of Zurich, Department of Economics.

Cagé, J and V Rueda (2016), “The long-term effects of the printing press in sub-Saharan Africa,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 8(3): 69-99.

Calvi, R, L Hoehn-Velasco and F G Mantovanelli (2022), “The Protestant legacy: missions, gender, and human capital in India”, Journal of Human Resources 57(6): 1946-1980.

Chaudhary, L and M Garg (2015), “Does history matter? Colonial education investments in India,” The Economic History Review 68(3): 937-961.

Dell, M (2010), “The persistent effects of Peru’s mining mita,” Econometrica 78(6): 1863-1903.

Dupraz, Y (2019), “French and British colonial legacies in education: Evidence from the partition of Cameroon”, The Journal of Economic History 79(3): 628-668.

Glaeser, E L, R La Porta, F Lopez-de-Silanes and A Shleifer (2004), “Do institutions cause growth?,” Journal of Economic Growth 9: 271-303.

Huillery, E (2009), “History matters: The long-term impact of colonial public investments in French West Africa,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1(2): 176-215.

Jedwab, R, F Meier zu Selhausen and A Moradi (2022), “The economics of missionary expansion: Evidence from Africa and implications for development,” Journal of Economic Growth 27(2): 149-192.

La Porta, R, F Lopez-de-Silanes, A Shleifer and R Vishny (1999), “The quality of government,” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 15(1): 222-279.

Nunn, N (2009), “The importance of history for economic development,” Annual Review of Economics 1(1): 65-92.

Rocha, R, C Ferraz, and R R Soares (2017), “Human capital persistence and development,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(4): 105-136.

Sraieb, N (1993), “L’idéologie de l’école en Tunisie coloniale (1881-1945),” Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée 68(1) : 239-254.

Waldinger, M (2017), “The long-run effects of missionary orders in Mexico,” Journal of Development Economics 127: 355-378.

Footnotes

Tunisia’s population is 98% Arab and 99% Sunni Muslim according to the CIA’s World Factbook (https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/tunisia, last access on 10 March 2024).

Photo by amin weslati: https://www.pexels.com/photo/bizerte-city-waterfront-houses-tunisia-8136613/

0 Comments